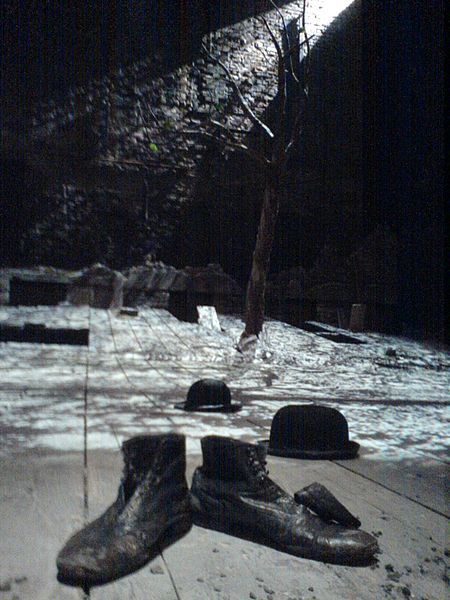

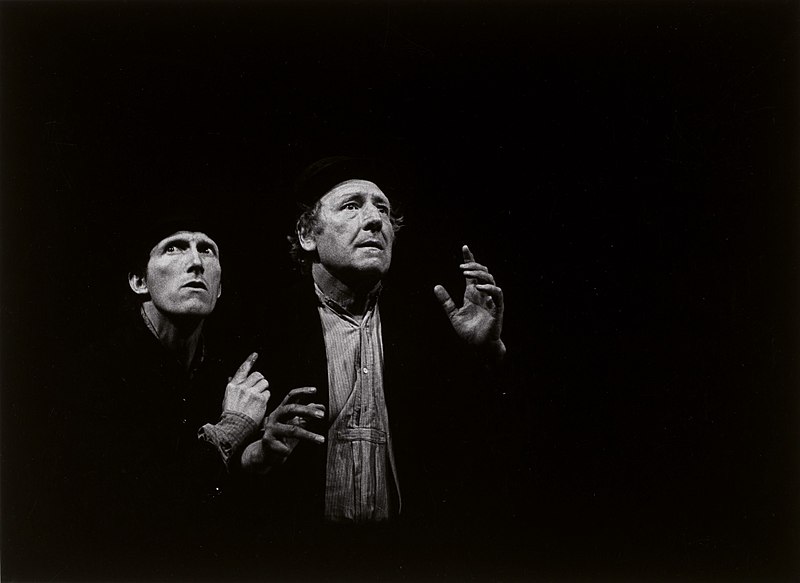

Before discussing the content of the work, such as it is, it is important to make some important notes about the form. Both in terms of the dialogue itself and in terms of the set, the work is a classic example of literary minimalism. For the setting, Beckett gives only the following direction: “A country road. A tree. Evening.” Productions, including Beckett’s own, have tended to follow these directions to the letter. That is, the set typically includes only a small tree and rock. Similarly, the dialogue is marked throughout by pauses and silences and consists largely in short sentences. Neither the set nor the language of characters is ornate or complex. Each element is stripped to its naked essence, we might say.

There are many ways to think about the meaning and importance of this minimalism. However, I think it is useful for our purposes to compare it to the phenomenological “suspension of judgment” as practiced by Edmund Husserl and Martin Heidegger’s concept of Angst. Recall that for Husserl, phenomenological method begins with a suspension of what he calls the “natural attitude.” We adopt instead a new “phenomenological attitude” by “bracketing” the taken for granted reality of our perceptions and beliefs. In the phenomenological attitude we approach the things we perceive and our judgments about them as phenomena, or appearances to consciousness, rather than facts. The idea is to strip away our everyday realism and to reflect on our consciousness of the world. Similarly, Heidegger describes Angst as a mood in which the everyday significance of the world collapses and discloses Da-sein to itself. In such a moment, Da-sein feels its thrown-ness into the world and anticipates its own death. All the ordinary meanings we attach to the world fall away and we confront our own existence. I would suggest that Beckett’s minimalism accomplishes a similar effect through dramatic and aesthetic means. All the context that would typically lend significance to the actions of the characters is stripped away. We are thus exposed to the truth about human existence, now without the props which might ordinarily cover it up.

A final important point: Often Beckett’s character’s make statements which, without dramatic context, say something other than their surface meaning. Consider the very opening of play. The direction is: “[giving up again].” This is followed by the initial line from Estragon, “Nothing to be done.” We come to find out that the line and the direction refer to Estragon’s struggle to remove his boot. However, of course, this moment should invoke for us Camus’ writing on the absurdity of existence and those moments in which we feel, as he puts it, “undermined.” A similar moment occurs in a discussion inspired by Estragon’s eating of a carrot. Ostensibly, the pair are discussing whether or not one can get used to eating bad food. Their different responses to this question, they decide, are a matter of character and temperament. Here is their exchange:

Vladimir: Nothing you can do about.

Estragon: No use struggling.

Vladimir: One is what one is.

Estragon: No use wriggling.

Vladimir: The essential doesn’t change.

Estragon: Nothing to be done

What at first presents itself as mere chatter about a carrot devolves into a statement of resigned fatalism. “Nothing to be done” is repeated but is now less a matter of the pointlessness of struggling and more resignation in the face of a seemingly immutable destiny. Of course, each of these moments might provoke us as audience members to question whether there isn’t, after all, something to be done.

To the degree that there is any coherent dramatic context for the events of the play it is supplied by the expected arrival of Godot. It is unclear throughout what Godot will say or do or what the ridiculous pair of Estragon and Vladimir will do after Godot comes. Yet, they seem unable to leave until they meet Godot. They exchange these words early on:

Estragon: Let’s go.

Vladimir: We can’t.

Estragon: Why not?

Vladimir: We’re waiting for Godot.

Here, we might return to our previous discussion of Heidegger’s distinction between “expectation” and “anticipation.” Clearly, the arrival of Godot is an “expected” event inasmuch as it is an occurrence within the world to which Vladimir and Estragon “look forward.” As we discussed with Heidegger, it is the anticipated whole which give to the parts of a temporal sequence their significance. We can see this at work in the play in that as audience members we too come to expect Godot and this expectation lends the words and actions of the duo any sense for us. Yet, by denying the audience any dramatic context for this expectation, the play short circuits the anticipated totality of the play. The audience is thus thrown back upon itself: Why am I even here watching this nonsense? The play is, as it were, designed to make us feel bored, alone, and anxious. And, possibly, to raise for us the question of the meaning of our own existence. Consider the supposed description of the twilight given by Pozzo [and recall our own discussions of the poetics of the twilight!],

Pozzo: An hour ago [he looks at his watch, prosaic] roughly [lyrical] after having poured forth even since [he hesitates, prosaic] say ten o’clock in the morning [lyrical] tirelessly torrents of red and which light it begins to lose its effulgence, to grow pale [gesture of the two hands lapsing by stages] pale, ever a little paler, a little paler until [dramatic pause, ample gesture of the two hands flung wide apart] pppfff! finished! it comes to rest. But — [hand raised in admonition] — but behind this veil of gentleness and peace night is charging [vibrantly] and will burst upon us [snaps his fingers] pop! like that! [his inspiration leaves him] just when we least expect it. [Silence. Gloomily.] That’s how it is on this bitch of an earth.

[Long silence.]

Estragon: So long as one knows.

Vladimir: One can bide one’s time.

Estragon: One knows what to expect.

Vladimir: No further need to worry.

Estragon: Simply wait.

There is much to remark in this passage. However, first, it’s useful to note that, again, the lines say a great deal more than their surface meaning. On the face of it, Pozzo is describing the way the sun sets in the part of the country where they are waiting for Godot. Vladimir and Estragon have said already that they have come from afar and are relatively unfamiliar with the place. But, when pulled from this context, Pozzo’s monologue looks much more like a poetic description of life and death. The ridiculous drama of his description, in which he swings his hands wildly and waxes back and forth between different forms of diction, serves to break the spell of supposed realism for the audience, perhaps so that this underlying meaning may present itself. A long silence follows this description, “that’s how it is on this bitch of an earth.” Much like Heidegger’s account of the “They,” Estragon and Vladimir must fill this silence: “One knows what to expect. No further need to worry. Simply wait.”

In the next blog post, I will return to the characters of Pozzo and Lucky. For now, it is worth noting a couple of important moments that will help us to think through their role in the play. After their departure and before the arrival of the boy, Vladimir and Estragon have a brief exchange:

[Long silence.]

Vladimir: That passed the time.

Estragon: It would have passed in any case.

Vladimir: Yes, but not so rapidly.

[Pause.]

Estragon: What do we do now?

Vladimir: I don’t know.

Estragon: Let’s go.

Vladimir: We can’t.

Estragon: Why not?

Vladimir: We’re waiting for Godot.

Estragon: [despairingly] Ah!

[Pause.]

The encounter with Pozzo and Lucky clearly occupies a central place in the first act. However, ultimately, it has contributed nothing to the overarching dramatic context: waiting for Godot. The events that have unfolded merely served to pass the time while waiting. There is no meaning or significance in their occurrence. They do not contribute to the anticipated temporal whole within which the events of the play make sense. And, again, if we ask ourselves why Vladimir and Estragon choose to continue on waiting as they are there is only the despairing tautology that they can’t leave because they are waiting for Godot.

The despair of their situation is now palpable. By the end, the duo returns to the theme of suicide: “Pity we haven’t got a bit of rope.” Estragon appears to think back on a previous suicide attempt when he was saved by Vladimir. This reflection on suicide harkens back to their previous discussion of hanging themselves from the tiny tree. In the initial discussion, Estragon fears to be the first person to hang as it may leave Vladimir alone. And, indeed, as they are unsure who is heavier, this fear works in both directions. By the end of the first act, this is their exchange:

Estragon: I sometimes wonder if we wouldn’t have been better off alone, each one for himself. [He crosses the stage and sits down on the mound.] We weren’t made for the same road.

Vladimir: [without anger] It’s not certain.

Estragon: No, nothing is certain.

[Vladimir slowly crosses the stage and sits beside Estragon.]

Vladimir: We can still part, if you think it would be better.

Estragon: It’s not worthwhile now.

[Silence.]

Vladimir: No, it’s not worthwhile now.

[Silence.]

Estragon: Well, shall we go?

Vladimir: Yes, let’s go.

[They do not move.]

Somehow, in a senseless world, the two are stuck together. Each is all the other has. But neither can be sure if they wouldn’t be better off alone.

Please feel free to leave comments and questions!